news

Weaponizing Domain Names: how bulk registration aids global spam campaigns

In 2019, Dave led research with the Interisle Consulting Group investigating criminal domain name abuse, focused on bulk registrations. These findings emphasized the need for more stringent measures to be put in place within...

In this guide

Jump to

We’re delighted to introduce Dave Piscitello as our first guest writer to the Spamhaus Blog. In 2019, Dave led research with the Interisle Consulting Group investigating criminal domain name abuse, focused on bulk registrations. These findings emphasized the need for more stringent measures to be put in place within the domain name industry, something that the current COVID-19 pandemic is further highlighting.

Cybercriminals will always take advantage

In their pursuit of criminals, cyber investigators need transparency when it comes to accessing domain registration data from WHOIS. Today, such concerns are coming from governments whose citizens are facing an avalanche of attacks exploiting the COVID-19/Coronavirus pandemic. In recent days, the U.S. Department of Justice filed a temporary restraining order against registrar Namecheap to suspend a domain that was used to host fake COVID test kits, citing that, "NameCheap, Inc. plays a critical role in the scheme by serving as the domain registrar of the website, which allows potential victims to access the website."

The Office of the New York Attorney General has also contacted registrar GoDaddy and others, expressing concern that "cybercriminals have been registering a significant number of domain names related to 'coronavirus' in recent weeks” and has outlined "steps to prevent bad actors from taking advantage of the current crisis" in their correspondence.

Here, we are looking at one of the several ways that miscreants exploit domain names, by utilizing bulk registration services to provide them with means to launch attacks from multiple origins.

The lure of bulk domain registrations

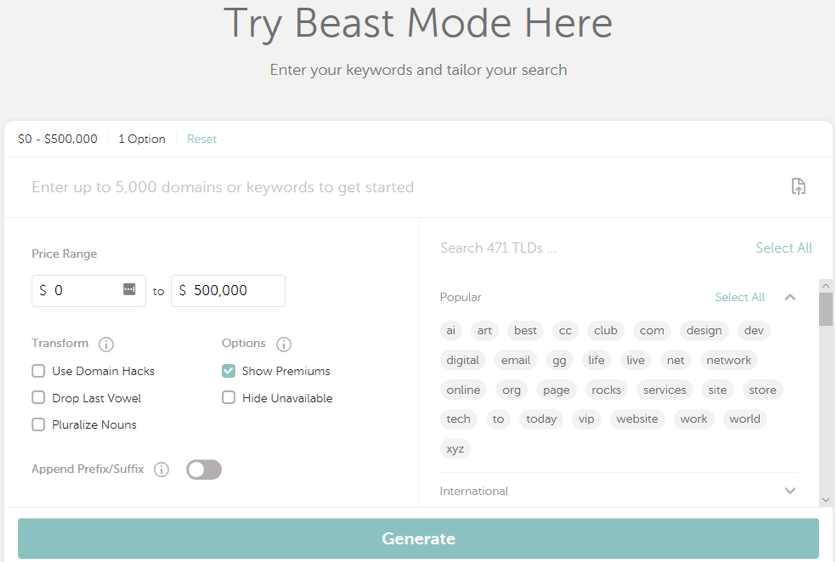

Cybercriminals rely upon domain names that can be rapidly acquired, used in an attack, and abandoned before they can be traced. Spam and ransomware campaigns, and criminal infrastructure operations – botnets and Ransomware or Phishing as a Service (RAAS, PhAAS) – particularly benefit from the ability to use bulk registration services offered by domain name registrars. Beast Mode, offered by the registrar NameCheap, Inc., illustrates how easily and cheaply domains can be acquired in this manner.

Figure 1: https://www.namecheap.com/domains/bulk-domain-search/

Figure 1: https://www.namecheap.com/domains/bulk-domain-search/

In our October 2019 study, Criminal Abuse of Domain Names, we observed and collected a sample of extraordinary daily spikes in domain names added to multiple reputation blocklists, including Spamhaus Domain Blocklist (DBL). We investigated these events by studying the following:

- Creation dates

- Sponsoring registrar

- Registrant (which was typically fraudulently composed data).

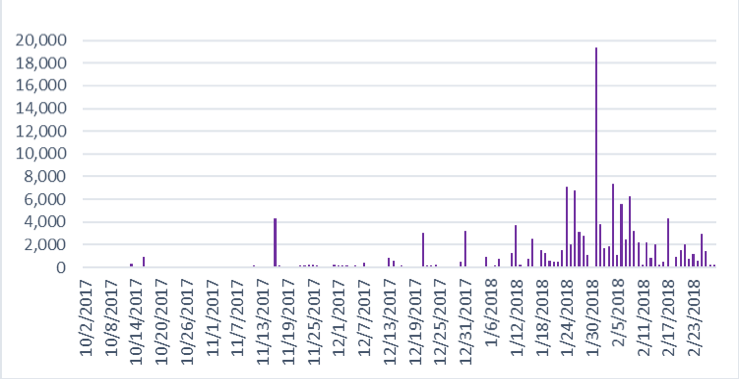

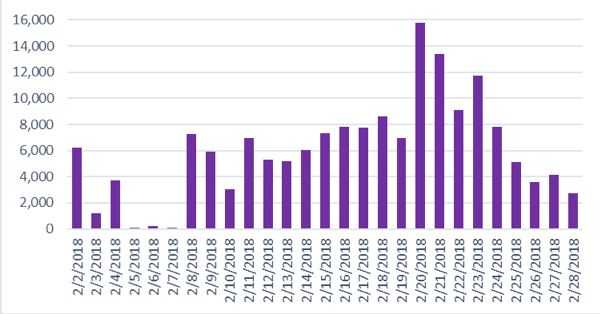

We were able to demonstrate that cybercriminals repeatedly registered hundreds or thousands of domain names in a matter of minutes. These were subsequently used to support snowshoe spam campaigns and phishing or ransomware attacks. Figure 2 provides an example of what these spikes look like at registration time, and Figure 3 illustrates the subsequent blocklisting dates of these same criminal domains.

Figure 2: Registration dates of blocklisted.TOP domains in the February 2018 sample

Figure 2: Registration dates of blocklisted.TOP domains in the February 2018 sample

Figure 3: Blocklisting of .TOP domains in February 2018 study sample

Figure 3: Blocklisting of .TOP domains in February 2018 study sample

A context for weaponizing domain names

The term ‘weaponize’ refers to the act of adapting something nominally benign – an off the shelf medicine, fertilizer, or even space – to serve as a tool in the pursuit of some malignant (criminal) activity. The broader context is that adapting these everyday items creates security threats, including national security threats to the well-being or lives of residents, visitors, and citizens.

When terrorists misuse fertilizers to construct improvised explosive devices, they are effectively “weaponizing” ammonium nitrate. When criminals divert pseudoephedrine to the manufacture of methamphetamine, they inflict harm or loss of life by weaponizing a medication intended to relieve suffering.

When cybercriminals acquire and employ thousands of internet domain names to distribute spam emitters, they are misusing domain names to cause financial loss or harm. In the extreme cases of ransomware attacks against healthcare or emergency systems or critical infrastructures, the potential harms include loss of life.

What’s the return on investment for a cybercriminal?

Cheap domain names, accessible in bulk, contribute to a criminal marketplace in which small investments can yield extraordinary returns. In the Interisle report, we consider the investment in a ransomware attack:

- Mailing lists can be purchased on the Dark Web, online or created using email harvesters, again available from programming repositories such as GitHub.

- 1000s of domain names can be acquired for pennies per domain from various registrars

- Malware can be purchased through RaaS as cheaply as $39.00. Similar opportunities exist for acquiring a Phishing kit, or these can be downloaded for free from repositories such as GitHub.

- Online tutorials for novices are available from YouTube.

Assuming an extortion fee of U.S. $200-500, a ransomware attack can be profitable with fewer than a dozen victims. Multiple, successful ransomware campaigns yielding thousands of victims is within reach, making this criminal activity a possible $1M/year enterprise.

The domain name industry’s obligation to protect the public from harm

Other industries recognize and accept their obligation to protect the public from criminal misuse of potentially dangerous products through mandatory or recommended validation regimes. U.S. pharmacies, for example, require valid proof of identity from any party that attempts to purchase quantities of pseudoephedrine that exceed well-defined limits. Legitimate businesses comply with these and like-minded regulations in the interest of public safety.

The domain name industry could accept a similar obligation by verifying registrant payment methods as part of the validation process; for example, registrars could decline transactions in which the registrant contact data does not match the authorized credit card user. They could also prohibit anonymous or non-traceable payment methods.

In our study, we used hundreds of thousands of current and historical domain registration (Whois) records to demonstrate that criminals routinely and repeatedly weaponize domain names using bulk registration. When registrant information was unavailable, correlation and attribution of bulk registrants were notably more difficult. We recommend that ICANN include a flag in registration records that indicates whether or not the domain name was registered as part of a bulk registration. The “bulk registrant” data element could be used to track or ban an abusive registrant across delegated gTLDs.

This lies well within ICANN’s security, stability, and resiliency bylaws remit to protect the public. Other industries track resources that can be weaponized; for example, tracking regulations apply to sellers of ammonium nitrate in the USA. These exist to protect the public against the construction of improvised explosive devices.

Most ammonium nitrate purchases are legitimate; so are most domain name registrations. But just as ammonium nitrate safety measures protect the public from acts of terrorism, this policy would protect the public from misuse of domain names for extortion, fraud, and other criminal acts. The domain name registration system was never intended to supply criminals with thousands of domains in matters of minutes. ICANN can and should try to adopt a policy to mitigate abusive bulk registration.

About Dave Piscitello

Dave has been involved in Internet technology for over 40 years. He participates actively in global collaborative efforts by security, operations, and law enforcement communities to mitigate Domain Name System abuse and malicious uses of Domain names. He publishes articles regularly on security, DNS, antiphishing, malware, Internet policy, and privacy, and maintains a highly active, insightful, and entertaining info site as The Security Skeptic. Dave is an Associate Fellow of the Geneva Centre for Security Policy, a member of the Boards of Directors of the Antiphishing Working Group (APWG) and the Coalition Against Unsolicited Commercial Email (CAUCE), and former invited participant in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Security Expert Group. In February 2019 Dave received the M3AAWG Mary Litynski Award.